A Notable Element in Scottish Art Nouveau Posters Was

| Edwardian era | |

|---|---|

| 1901–1910 | |

Rex Edward VII by Fildes (c. 1901, particular) | |

| Preceded by | Victorian era |

| Followed past | Showtime World War |

| Monarch(s) |

|

| Leader(s) |

|

The Edwardian era or Edwardian period of British history spanned the reign of King Edward Seven, 1901 to 1910, and is sometimes extended to the offset of the Showtime Earth War. The death of Queen Victoria in January 1901 marked the finish of the Victorian era. Her son and successor, Edward VII, was already the leader of a fashionable elite that set a fashion influenced by the art and fashions of continental Europe. Samuel Hynes described the Edwardian era as a "leisurely time when women wore pic hats and did not vote, when the rich were not ashamed to live conspicuously, and the sun actually never set on the British flag."[ane]

The Liberals returned to ability in 1906 and fabricated significant reforms. Below the upper form, the era was marked past pregnant shifts in politics amid sections of lodge that had largely been excluded from power, such as labourers, servants, and the industrial working course. Women started to play more than of a role in politics.[two]

The Edwardian era was the last catamenia of British history to be named after the reigning monarch. The subsequent reigns of George V and George VI are not commonly termed Georgian era, this name being reserved for the fourth dimension of the 18th-century kings of that name. Similarly, Elizabethan era refers solely to the 16th-century queen Elizabeth I and is not extended to the current Elizabeth II.

Perceptions [edit]

The Edwardian period is sometimes portrayed every bit a romantic golden age of long summer afternoons and garden parties, basking in a sun that never attack the British Empire. This perception was created in the 1920s and later by those who remembered the Edwardian age with nostalgia, looking back to their childhoods across the abyss of the Cracking State of war.[3] The Edwardian age was likewise seen every bit a mediocre period of pleasure between the neat achievements of the preceding Victorian age and the catastrophe of the following war.[4]

Recent assessments emphasise the keen differences between the wealthy and the poor during this period and describe the age as heralding swell changes in political and social life.[2] [5] Historian Lawrence James has argued that the leaders felt increasingly threatened by rival powers such equally Germany, Russia, and the United states of america.[6] Nevertheless, the sudden arrival of World State of war I in the summer of 1914 was largely unexpected, except by the Royal Navy, because information technology had been prepared and gear up for war.

Politics [edit]

There was a growing political sensation amongst the working form, leading to a rise in trade unions, the Labour motion and demands for improve working conditions. The aristocracy remained in control of elevation government offices.[vii]

Bourgeois Party [edit]

The Conservatives – at the fourth dimension called "Unionists" – were the dominant political party from the 1890s until 1906. The party had many strengths, appealing to voters supportive of imperialism, tariffs, the Church building of England, a powerful Royal Navy, and traditional hierarchical club. There was a powerful leadership base in the landed elite and landed gentry in rural England, plus strong support from the Church of England and military interests. Historians accept used election returns to demonstrate that Conservatives did surprisingly well in working-class districts.[8] [9] They had an entreatment as well to the better-off chemical element of traditional working-class Britons in the larger cities.[ten]

In rural areas, the national headquarters made highly effective use of paid travelling lecturers, with pamphlets, posters, and especially lantern slides, who were able to communicate effectively with rural voters – particularly the newly enfranchised agricultural workers.[11] In the first years of the twentieth century, the Conservative regime, with Arthur Balfour as Prime number Government minister, had numerous successes in foreign policy, defense, and education, as well as solutions for the issues of alcohol licensing and land ownership for the tenant farmers of Ireland.[12]

Nonetheless, the weaknesses were accumulating, and proved and so overwhelming in 1906 that the party did not render to complete power until 1922.[thirteen] The Conservative Political party was losing its drive and enthusiasm, especially after the retirement of the charismatic Joseph Chamberlain. In that location was a bitter split on "tariff reform" (that is, imposing tariffs or taxes on all imports), that drove many of the free traders over to the Liberal army camp. Tariff reform was a losing issue that the Conservative leadership inexplicably clung to.[14]

Bourgeois support weakened amid the acme tier of the working-course and lower middle-form, and there was dissatisfaction amidst intellectuals. The 1906 general ballot was a landslide victory for the Liberal Party, which saw its total vote share increase by 25%, while the Bourgeois total vote held steady.[xv]

Labour Party [edit]

Leaders of the Labour Party in 1906

The Labour Political party was emerging from the apace growing trade wedlock movement after 1890. In 1903 information technology entered the Gladstone–MacDonald pact with the Liberals, assuasive for cross-political party support in elections, and the emergence of a small Labour contingent in Parliament. Information technology was a temporary organization until the 1920s, when the Labour Party was strong enough to act on its own, and the Liberals were in an irreversible decline. Subtle social changes in the working-class were producing a younger generation that wanted to act independently.[16]

Michael Childs argues that the younger generation had reason to prefer Labour over Liberal political styles. Social factors included secularised elementary education (with a disappearing role for Dissenting schools that inculcated Liberal viewpoints); the "New Unionism" after 1890 brought unskilled workers into a movement previously dominated by the skilled workers;[17] and new leisure activities, particularly the music hall and sports, involved youth while repelling the older generation of Liberal voters.[16]

Liberal Party [edit]

The Liberal Political party lacked a unified ideological base in 1906.[eighteen] It contained numerous contradictory and hostile factions, such as imperialists and supporters of the Boers;[19] near-socialists and laissez-faire classical liberals; suffragettes and opponents of women's suffrage;[xx] antiwar elements and supporters of the armed forces alliance with France.[21] Nonconformist Dissenters – Protestants exterior the Anglican fold – were a powerful element, dedicated to opposing the established church in the fields of education and taxation. However, the Dissenters were losing support and played a lesser and lesser role in party affairs after 1900.[22]

The party also included Roman Catholics, including the notable Catholic intellectual Hilaire Belloc, who sabbatum as a Liberal MP between 1906 and 1910. They included secularists from the labour movement. The middle-form business, professional and intellectual communities were generally strongholds, although some old aristocratic families played of import roles besides. The working-class element was moving chop-chop toward the newly emerging Labour Party. I unifying element was widespread understanding on the use of politics and Parliament as a means to upgrade and improve society and to reform politics.[23] [24] In the Business firm of Lords, the Liberals lost about of their members, who in the 1890s "became Conservative in all just name." The government could force the unwilling rex to create new Liberal peers, and that threat did bear witness decisive in the battle for dominance of Commons over Lords in 1911.[25]

Boer State of war [edit]

The medical staff of No. 1 Stationary Hospital at Ladysmith

The government entered the Second Boer War with corking confidence, trivial expecting that the ii minor rural Boer republics in southern Africa with a combined White population smaller than that of London would hold off the concentrated power of the British Empire for two and half years, and have 400,000 Imperial troops to secure victory.[26] The war dissever the Liberal Party into anti- and pro-war factions. Great orators, such as Liberal David Lloyd George, who spoke confronting the war, became increasingly influential. Nevertheless, Liberal Unionist Joseph Chamberlain, who was largely in accuse of the war, maintained his agree on power.[27]

When General Kitchener took command in 1900, he initiated a scorched globe policy in order to foil Boer guerilla tactics. Captured Boer combatants were transported overseas to other British possessions as prisoners of state of war. Still he relocated noncombatant Boers—mostly women and children—into heavily guarded internment camps. The internment camps were overcrowded with bad sanitation and meagre nutrient rations. Contagious diseases such as measles, typhoid and dysentery were endemic.[28]

Many of the internees died. Emily Hobhouse visited the camps and brought the conditions to the attention of the British public. Public outcry resulted in the Fawcett Commission which corroborated Hobhouse's written report and eventually led to improved conditions.[29] The Boers surrendered and the Boer Republics were annexed past the British Empire. Jan Smuts—a leading Boer general—became a senior official of the new authorities and fifty-fifty became a summit British official in the World War.[30]

In 1901, the six British self-governing colonies of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Commonwealth of australia, and Western Australia united to grade the Commonwealth of Australia, with almost complete control of its internal affairs, simply with foreign policy and defence force handled by London. Edmund Barton was the start prime minister.[31]

The Liberal reforms [edit]

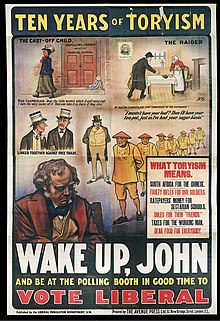

A Liberal poster c. 1905–1910

The Liberal Party under Henry Campbell-Bannerman rallied Liberals around the traditional platform of free trade and state reform and led them to the greatest balloter victory in Liberal Political party history.[32] The Prime Government minister was overshadowed by his frontbench, almost notably H. H. Asquith at the Exchequer, Edward Greyness at the Foreign Office, Richard Burdon Haldane at the War Office and David Lloyd George at the Lath of Trade. Campbell-Bannerman retired in 1908 and was succeeded by Asquith. He stepped up the government'south radicalism, specially in the "People'southward Budget" of 1909 that proposed to fund expanded social welfare programmes with new taxes on land and high incomes. It was blocked by the Bourgeois-dominated House of Lords, but eventually became police in Apr 1910.

Well-nigh one-half of the Liberal MPs elected in 1906 were supportive of the "new liberalism", which advocated government activity to improve people's lives.[33]

Liberals in 1906–1911 passed major legislation designed to reform politics and society, such as the regulation of working hours, National Insurance and the beginnings of the welfare country, too as curtailing the power of the House of Lords. Women'south suffrage was not on the Liberal agenda.[34] There were numerous major reforms helping labour, typified past the Merchandise Boards Act 1909 that set minimum wages in certain trades with the history of "sweated" or "sweatshop" rates of specially depression wages, because of surplus of available workers, the presence of women workers, or the lack of skills.[35]

At start it applied to four industries: concatenation-making, set-made tailoring, newspaper-box making, and the machine-fabricated lace and finishing merchandise.[35] Information technology was afterward expanded to coal mining and and so to other industries with preponderance of unskilled manual labour past the Trade Boards Deed 1918. Nether the leadership of David Lloyd George Liberals extended minimum wages to farm workers.[36]

Conservative peers in the House of Lords tried to stop the People'south Budget. The Liberals passed the Parliament Deed 1911 to sharply reduce the power of the House of Lords to block legislation. The toll was loftier, all the same, equally the government was required by the rex to telephone call two general elections in 1910 to validate its position and ended upwards frittering away almost of its large majority, with the rest of power held by Labour and Irish Parliamentary Political party members.

Strange relations [edit]

Ties with French republic and Russia against Germany [edit]

Germany'southward Chancellor Otto von Bismarck dominated European diplomacy from 1872 to 1890, with a policy of using the European residue of power to keep the peace. There were no wars. Bismarck was removed by an ambitious young Kaiser Wilhelm in 1890, effectively decentralizing the Bismarckian Order that had been shrewdly managed, and empowering French efforts to isolate Germany. With the formation of the Triple Entente, Germany began to feel encircled: to the Due west lay France, with whom rivalry was enkindling later a generation of dormancy post-obit the Franco-Prussian State of war, to the Due east saturday Russia, whose rapid industrialization worried Berlin and Vienna.[37]

Joseph Chamberlain, who played a major role in foreign policy in the late 1890s under the Salisbury government, repeatedly tried to open talks with Deutschland about some sort of brotherhood. Berlin was non interested.[38] Meanwhile, Paris went to nifty pains to woo Russia and Peachy Uk. Key markers were the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1894, the 1904 Entente Cordiale linking French republic and Britain, and finally the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907 which became the Triple Entente. French republic thus had a formal brotherhood with Russia, and an breezy alignment with Uk, against Frg and Austria.[39] By 1903 good relations had been established with the The states and Nippon.[40]

U.k. abased the policy of holding aristocratic from the continental powers, so chosen "First-class Isolation", in the 1900s later being isolated during the Boer State of war. Britain ended agreements, limited to colonial affairs, with her 2 major colonial rivals: the Entente Cordiale with France in 1904 and the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907. Britain's alignment was a reaction to an assertive High german foreign policy and the buildup of its navy from 1898 which led to the Anglo-German naval artillery race.[41] British diplomat Arthur Nicolson argued it was "far more disadvantageous to united states of america to accept an unfriendly France and Russia than an unfriendly Frg".[42]

The impact of the Triple Entente was to better British relations with France and its marry Russia and to demote the importance to Britain of practiced relations with Frg. After 1905, foreign policy was tightly controlled by the Liberal Foreign Secretary Edward Grey (1862-1933), who seldom consulted with his political party leadership. Grayness shared the strong Liberal policy against all wars and against military alliances that would force Britain to take a side in state of war. Withal, in the case of the Boer War, Grey held that the Boers had committed an aggression that information technology was necessary to repulse. The Liberal party split on the issue, with a large faction strongly opposed to the war in Africa [43]

The Triple Entente between Uk, France and Russia is often compared to the Triple Alliance betwixt Germany, Austria–Hungary and Italy, just historians caution against the comparison. The Entente, in contrast to the Triple Brotherhood or the Franco-Russian Alliance, was non an alliance of common defense and Great britain therefore felt complimentary to make her own strange policy decisions in 1914. The Liberals were highly moralistic, and by 1914 they have been increasingly convinced that German aggression violated international norms, and specifically that its invasion of neutral Belgium was completely unacceptable in terms of morality, Britain and Germany'south obligations nether the Treaty of London, and in terms of British policy against whatsoever one power decision-making the continent of Europe.[44]

Until the last few weeks before it started in August 1914, almost no one saw a world state of war coming. The expectation among the generals was that considering of industrial advances any future war would produce a quick victory for the side that was better-prepared, better armed, and faster to move. No one saw that the innovations of contempo decades—high explosives, long-range artillery and machine guns—were defensive weapons that practically guaranteed defeat of massed infantry attacks with very high casualties.[45]

[edit]

The British Dreadnought (1906) fabricated all battleships obsolete because information technology had ten long-range 12-inch big guns, mechanical estimator-similar range finders, high speed turbine engines that could make 21 knots, and armour plates 11 inches thick.

Later 1805 the dominance of Britain's Royal Navy was unchallenged; in the 1890s Germany decided to friction match it. Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz (1849 – 1930) dominated German naval policy from 1897 until 1916.[46] Before the German Empire formed in 1871, Prussia never had a real navy, nor did the other German states. Tirpitz turned the modest fiddling armada into a world-course force that could threaten the British Imperial Navy. The British responded with new technology typified by the Dreadnought revolution. It made every battleship obsolete and, supplemented by the global network of coaling stations and telegraph cables, enabled Britain to stay well in the lead in naval affairs.[47] [48]

Apart from a determination to retain a strong naval reward, the British lacked a military strategy or plans for a major state of war.[49]

Economy [edit]

The Edwardian era stands out as a time of peace and prosperity. There were no astringent depressions, and prosperity was widespread. United kingdom's growth rate, manufacturing output and GDP (only non Gross domestic product per capita) fell behind its rivals, the United States and Frg, merely the nation still led the world in trade, finance and shipping, and had stiff bases in manufacturing and mining.[l] The industrial sector was slow to adjust to global changes, and there was a hit preference for leisure over entrepreneurship amidst the elite.[51]

Nevertheless, major achievements should be underlined. London was the financial centre of the world—far more efficient and wide-ranging than New York, Paris or Berlin. Uk had congenital upwardly a vast reserve of overseas credits in its formal Empire, every bit well as in its informal empire in Latin America and other nations. It had huge fiscal holdings in the United States, especially in railways. These assets proved vital in paying for supplies in the first years of the World State of war. The amenities, especially in urban life, were accumulating—prosperity was highly visible. The working classes were get-go to protest politically for a greater vocalization in government, but the level of industrial unrest on economic issues was not high until about 1908.[51]

Social change and improved health [edit]

Past the late-1880s, the Industrial Revolution had created new technologies that inverse the fashion people lived. The growth of industry shifts in manufacturing factories, special-purpose machinery and technological innovations, which led to increased productivity. Gender roles shifted equally women fabricated use of the new technology to upgrade their lifestyle and their career opportunities.

Mortality declined steadily in urban England and Wales 1870–1917. Robert Millward and Frances N. Bell looked statistically at those factors in the physical environment (especially population density and overcrowding) that raised death rates straight, as well as indirect factors such equally price and income movements that affected expenditures on sewers, water supplies, food, and medical staff. The statistical data bear witness that increases in the incomes of households and increases in town tax revenues helped cause the turn down of mortality.[52]

The new money permitted higher spending on food, and also on a wide range of wellness-enhancing appurtenances and services such as medical care. The major improvement in the physical environs was the quality of the housing stock, which rose faster than the population; its quality was increasingly regulated past key and local authorities.[52] Infant bloodshed fell faster in England and Wales than in Scotland. Clive Lee argues that 1 factor was the connected overcrowding in Scotland's housing.[53] During the First World War, baby mortality fell sharply beyond the country. J. M. Wintertime attributes this to the full employment and higher wages paid to war workers.[54]

Rising condition of women [edit]

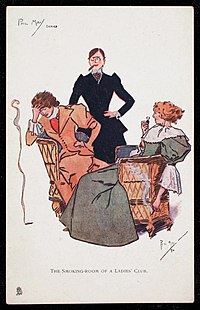

Oilette postcard with fine art by Phil May, published by Raphael Tuck & Sons, circa 1910s

For housewives, sewing machines enabled the production of fix-made habiliment and made it easier for women to sew their ain dress; more than mostly, argues Barbara Burman, "home dressmaking was sustained as an important aid for women negotiating wider social shifts and tensions in their lives."[55] Increased literacy in the middle class gave women wider access to information and ideas. Numerous new magazines appealed to her tastes and helped define femininity.[56]

The inventions of the typewriter, telephone, and new filing systems offered eye-grade women increased employment opportunities.[57] [58] So too did the rapid expansion of the schoolhouse system,[59] and the emergence of the new profession of nursing. Education and status led to demands for female roles in the rapidly expanding world of sports.[sixty]

Women were very active in church diplomacy, including attendance at services, Sunday schoolhouse pedagogy, fund raising, pastoral care, social work and support for international missionary activities. They were nearly completely excluded from practically all leadership roles.[61]

Women's suffrage [edit]

As heart-class women rose in status, they increasingly supported demands for a political voice.[62] [63] At that place was significant support for adult female suffrage in all the parties, but the Liberal Party was in control later 1906 and a handful of its leaders, specially H. H. Asquith, blocked it.[64]

In that location were numerous organisations which did their work quietly. Later on 1897, they were increasingly linked together by the National Wedlock of Women'south Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) led by Millicent Fawcett. However, front page publicity was seized by the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Founded in 1903, it was tightly controlled past the three Pankhursts, Emmeline Pankhurst (1858–1928), and her daughters Christabel Pankhurst (1880–1958) and Sylvia Pankhurst (1882–1960).[65]

It specialised in highly visible publicity campaigns such every bit large parades. This had the outcome of energising all dimensions of the suffrage move. While there was a majority of support for suffrage in Parliament, the ruling Liberal Party refused to allow a vote on the issue; the event of which was an escalation in the suffragette campaign. The WSPU, in dramatic contrast to its allies, embarked on a campaign of violence to publicise the result, fifty-fifty to the detriment of its ain aims.[66] [67]

Birth control [edit]

Although abortion was illegal, it was nonetheless the virtually widespread course of birth command in use.[68] Used predominantly by working-class women, the process was used non only every bit a means of terminating pregnancy, only also to prevent poverty and unemployment. Those who transported contraceptives could be legally punished. Contraceptives became more expensive over fourth dimension and had a high failure rate. Unlike contraceptives, ballgame did not demand any prior planning and was less expensive. Newspaper advertisements were used to promote and sell abortifacients indirectly.[69]

Not all of lodge was accepting of contraceptives or abortion, and the opposition viewed both as part of one and the same sin. Ballgame was much more common amidst the middle-classes than among those living in rural areas, where the process was not readily available. Women were oft tricked into purchasing ineffective pills. In improver to fearing legal reprimands, many physicians did non condone abortion because they viewed it every bit an immoral procedure potentially endangering a woman'due south life.[69] Considering ballgame was illegal and physicians refused to perform the procedure, local women acted equally abortionists, oft using crochet hooks or similar instruments.[68]

Feminists of the era focused on educating and finding jobs for women, leaving aside the controversial problems of contraceptives and abortion, which in pop stance were often related to promiscuity and prostitution. The Church building condemned abortion every bit immoral and a class of rebellion against the child-bearing part women were expected to presume. Many considered abortion to be a selfish human activity that allowed a woman to avoid personal responsibility, contributing to a decline in moral values.[68] Abortion was often a solution for women who already had children and did not desire more. Consequently, the size of families decreased drastically.[69]

Poverty among working-class women [edit]

The 1834 Poor Police defined who could receive monetary relief. The act reflected and perpetuated prevailing gender weather. In Edwardian society, men were the source of wealth. The law restricted relief for unemployed, able-bodied male workers, due to the prevailing view that they would find piece of work in the absenteeism of financial assistance. Notwithstanding, women were treated differently. After the Poor Law was passed, women and children received most of the assistance.[70]

The law did not recognise single contained women, and put women and children into the same category. If a man was physically disabled, his wife was also treated every bit disabled nether the coverture laws, even though coverture was fast becoming outmoded in the Edwardian era. Unmarried mothers were sent to the workhouse, receiving unfair social treatment such as being restricted from attending church on Sundays.[seventy]

During marriage disputes, women frequently lost the rights to their children, even if their husbands were calumniating.[70] However, women were increasingly granted custody of their children under seven years of historic period; this trend was colloquially known as the "tender years doctrine," where it was believed that a child was all-time left under maternal intendance until the historic period of seven.[71]

At the time, unmarried mothers were the poorest sector in society, disadvantaged for at to the lowest degree iv reasons. Outset, women lived longer, often leaving them widowed with children. Second, women had fewer opportunities to piece of work, and when they did find it, their wages were lower than male workers' wages. Thirdly, women were often less likely to marry or remarry afterward being widowed, leaving them as the main providers for the remaining family members. Finally, poor women had deficient diets, considering their husbands and children received disproportionately large shares of food. Many women were malnourished and had limited access to health care.[70]

Female servants [edit]

Edwardian United kingdom had large numbers of male and female domestic servants, in both urban and rural areas.[72] Centre- and upper-class women relied on servants to run their homes smoothly. Servants were provided with nutrient, clothing, housing, and a small wage, and lived in a self-enclosed social arrangement within their employer's firm.[73] Yet, the number of domestic servants brutal in the Edwardian era due to fewer immature people willing to be employed in this chapters.[74]

Fashion [edit]

A cartoon in Punch (1911) compares changes in fashion between 1901 and 1911. "The dowdy voluminous clothes of the earlier date, making the grandmother an old lady and the mother seem apparently, had been replaced by much simpler looser habiliment producing a sense of release for all three females."[75]

The upper classes embraced leisure sports, which resulted in rapid developments in style, as more mobile and flexible habiliment styles were needed.[76] [77] During the Edwardian era, women wore a very tight corset, or bodice, and dressed in long skirts. The Edwardian era was the concluding time women wore corsets in everyday life.[ citation needed ] Co-ordinate to Arthur Marwick, the most striking alter of all the developments that occurred during the Great War was the modification in women's dress, "for, however far politicians were to put the clocks back in other steeples in the years after the war, no one ever put the lost inches back on the hems of women's skirts".[78]

Fabrics were usually sugariness pea shades in chiffon, mousse line de sore, tulle with plumage boas and lace. 'Loftier and boned collars for the solar day; plugging off shoulder décolleté for the evening'.[79] The Tea Gown's cutting was relatively loose compared to the evening gown, and was worn without a corset. The silhouette was flowing, and was usually busy with lace or with the cheaper Irish crochet.[fourscore]

Long child gloves, trimmed hats, and parasols were oftentimes used as accessories. Parasols are different than umbrellas; they are used for protection from the sun, rather from the rain, though they were often used as ornamentation rather than for office. By the end of the Edwardian era, the hat grew bigger in size, a trend that would proceed in the 1910s.

The Edwardians developed new styles in clothing blueprint.[81] The Edwardian Era saw a decrease in the trend for voluminous, heavy skirts.[82]

- The two-piece dress came into vogue. At the start of the decade, skirts were trumpet-shaped.

- Skirts in 1901 often had decorated hems with ruffles of textile and lace.

- Some dresses and skirts featured trains.

- Tailored jackets, first introduced in 1880, increased in popularity and by 1900, tailored suits known as tailormades became popular.[83]

- In 1905, skirts fell in soft folds that curved in, then flared out nearly the hemlines.

- From 1905 – 1907, waistlines rose.

- In 1911, the hobble skirt was introduced; a tight plumbing equipment skirt that restricted a woman's pace.

- Lingerie dresses, or tea gowns fabricated of soft fabrics, festooned with ruffles and lace were worn indoors.[84]

- Around 1913 women'south dresses acquired a lower and sometimes V-shaped neckline in dissimilarity to the high collars a generation earlier. This was considered scandalous by some, and caused outrage among clergy throughout Europe.[85]

Newspapers [edit]

The turn of the century saw the rise of pop journalism aimed at the lower middle class and tending to deemphasise highly detailed political and international news, which remain the focus of a handful of low-circulation prestige newspapers. These were family-owned and operated, and were primarily interested not in profits but in influence on the nation's elite by their control of the news and editorials on serious topics.[86]

The new press, on the other mitt, reached vastly larger audiences past emphasis on sports, crime, sensationalism, and gossip near famous personalities. Detailed accounts of major speeches and circuitous international events were not printed. Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe was the master innovator.[86] He used his Daily Mail service and Daily Mirror to transform the media along the American model of "Yellow Journalism". Lord Beaverbrook said he was "the greatest figure who ever strode downward Armada Street".[87] Harmsworth made a cracking deal of money, but during the Offset Globe War he also wanted political power. For that he purchased the highest prestige newspaper, The Times.[88] P. P. Catterall and Colin Seymour-Ure conclude that:

More than than anyone [he] ... shaped the modern press. Developments he introduced or harnessed remain cardinal: wide contents, exploitation of advert revenue to subsidize prices, ambitious marketing, subordinate regional markets, independence from party command.[89]

The arts [edit]

The Edwardian era corresponds to the French Belle Époque. Despite its brief pre-eminence, the flow is characterised by its own unique architectural style, style, and lifestyle. Art Nouveau had a particularly stiff influence. Artists were influenced by the development of the automobile and electricity, and a greater awareness of human being rights.

In Nov 1910, Roger Fry organised the exhibition Manet and the Mail-Impressionists at the Grafton Galleries, London. This exhibition was the first to prominently characteristic Gauguin, Manet, Matisse, and Van Gogh in England and brought their art to the public. He followed it up with the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in 1912.

George Frampton'south statue of Peter Pan, "erected in Hyde Park in 1912 ... immediately became a source of contention, sparking debate virtually the office of public statuary and its role in spaces of recreation."[ninety]

Literature [edit]

In fiction, some of the best-known names are J. M. Barrie, Arnold Bennett, G. G. Chesterton, Arthur Conan Doyle, Joseph Conrad, E. Thousand. Forster, John Galsworthy, Kenneth Grahame, K. R. James, Rudyard Kipling, A. A. Milne, E. Nesbit, Beatrix Potter, Saki, George Bernard Shaw, H. Yard. Wells and P. Grand. Wodehouse. Autonomously from these famous writers, this was a period when a not bad number of novels and short stories were existence published, and a significant distinction between "highbrow" literature and popular fiction emerged. Among the near famous works of literary criticism was A. C. Bradley'south Shakespearean Tragedy (1904).[91]

Music [edit]

Alive performances, both amateur and professional, were popular. Henry Wood, Edward Elgar, Gustav Holst, Arnold Bax, George Butterworth, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Thomas Beecham were all agile. Military and brass bands often played outside in parks during the summer.[92] The new technology of wax cylinders and gramophone records played on phonographs and talking machines, made alive performances permanently bachelor for repetition at any time.

Performing arts [edit]

Cinema was primitive and audiences preferred live performances to picture shows. Music hall was very popular and widespread; influential performers included male person impersonator Vesta Tilley and comic Little Tich.[93]

The most successful playwright of the era was W. Somerset Maugham. In 1908, he had four plays running simultaneously in London, and Punch published a cartoon of Shakespeare biting his fingernails nervously equally he looked at the billboards. Maugham'south plays, like his novels, unremarkably had a conventional plot structure, just the decade as well saw the rise of the and then-called New Drama, represented in plays past George Bernard Shaw, Harley Granville Barker, and Continental imports past Henrik Ibsen and Gerhardt Hauptmann. The histrion/director system, equally managed past Sir Henry Irving, Sir George Alexander, and Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, was in decline.

Architecture [edit]

Notable architects included Edwin Lutyens, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and Giles Gilbert Scott. In spite of the popularity of Fine art Nouveau in Europe, the Edwardian Baroque style of architecture was widely favoured for public structures and was a revival of Christopher Wren–inspired designs of the belatedly 17th and early 18th centuries. The modify or reversal in sense of taste from the Victorian eclectic styles corresponded with the historical revivals of the period, near prominently earlier Georgian and Neoclassical styles of the late 18th and early on 19th centuries.[94]

White City Stadium, used for the 1908 Summer Olympics, was the starting time Olympic Stadium in the UK. Built on the site of the Franco-British Exhibition, it had a seating capacity of 68,000 and was opened by Rex Edward VII on 27 April 1908. It was the largest structure of its blazon in the earth at the time, and was designed to be awe-inspiring and thereby enhance the love of big-calibration spectacle that characterised Edwardian London.[95]

Pic [edit]

Filmmakers Mitchell and Kenyon documented many scenes from Britain and Ireland from 1900 to 1907, sports, parades, factory exits, parks, city streets, canoeing and the like. Their films have survived in very skillful quality restored from the original negatives.[96] [97]

Science and engineering [edit]

The flow featured many innovations. Ernest Rutherford published his studies on radioactivity. The start transatlantic wireless signals were sent by Guglielmo Marconi, and the Wright brothers flew for the first time.[98]

By the stop of the era, Louis Blériot had crossed the English Channel by air; the largest transport in the globe, RMS Olympic, had sailed on its maiden voyage and her larger sis RMS Titanic was under structure; automobiles were common; and the S Pole was reached for the showtime fourth dimension by Roald Amundsen's and then Robert Falcon Scott'southward teams.

Sport [edit]

The 1908 Summer Olympic Games were held in London. Popularity of sports tended to conform to class divisions, with tennis and yachting popular amid the very wealthy and football favoured by the working form.[99]

Football [edit]

Aston Villa maintained their position as the pre-eminent football team of the era, winning the FA Cup for the fourth time in 1904–05 and their sixth League title in 1909–10. The club colours of claret and sky blue were adopted by Burnley as a tribute to their success in 1910. Sunderland accomplished their quaternary league title in 1901–02. The era also saw Liverpool (1900–01, 1905–06), Newcastle United (1904–05, 1906–07, 1908–09) and Manchester United (1907–08) winning their first league titles.[100]

See besides [edit]

- Historiography of the United Kingdom

- Progressive Era, for the United States around the aforementioned time

References [edit]

- ^ "Manor Business firm. Edwardian Life | PBS". www.pbs.org.

- ^ a b Roy Hattersley, The Edwardians (2004).

- ^ J. B. Priestley The Edwardians (1970), pp. 55–56, 288–290.

- ^ Battiscombe, Georgina (1969). Queen Alexandra . London: Constable. p. 217. ISBN978-0-09-456560-9.

- ^ G. R. Searle, A New England?: peace and war, 1886–1918 (Oxford UP, 2004)

- ^ James, Lawrence (1994). The Rise and Autumn of the British Empire. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN978-0-349-10667-0.

- ^ David Brooks, The age of upheaval: Edwardian politics, 1899–1914 (Manchester University Press, 1995).

- ^ Jon Lawrence, "Class and gender in the making of urban Toryism, 1880–1914." English Historical Review 108.428 (1993): 629–652.

- ^ Matthew Roberts, "Pop Conservatism in Britain, 1832–1914." Parliamentary History 26.iii (2007): 387–410.

- ^ Marc Brodie, "Voting in the Victorian and Edwardian East Stop of London." Parliamentary History 23.ii (2004): 225–248.

- ^ Kathryn Rix, "'Get Out into the Highways and the Hedges': The Diary of Michael Sykes, Conservative Political Lecturer, 1895 and 1907–8." Parliamentary History xx#2 (2001): 209–231.

- ^ Robert Blake, The Bourgeois Party: from Peel to Major(2nd ed. 1985) pp 174–75

- ^ David Dutton, "Unionist Politics and the aftermath of the General Election of 1906: A Reassessment." Historical Journal 22#4 (1979): 861–876.

- ^ Andrew Due south. Thompson, "Tariff reform: an regal strategy, 1903–1913." Historical Journal xl#4 (1997): 1033–1054.

- ^ Blake, The Conservative Party: from Peel to Major(1985) pp 175–89

- ^ a b Michael Childs, "Labour Grows Upwards: The Electoral System, Political Generations, and British Politics 1890–1929." Twentieth Century British History 6#ii (1995): 123–144.

- ^ G.R. Searle, A new England?: peace and war, 1886–1918 (2004), pp 185–87.

- ^ Ian Packer, "The neat Liberal landslide: the 1906 General Election in perspective." Historian 89#1 (2006): eight–16.

- ^ John Due west. Auld, "The Liberal Pro-Boers." Journal of British Studies 14#ii (1975): 78–101.

- ^ Martin Pugh, Votes for women in United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland 1867–1928 (1994)

- ^ Nabil M. Kaylani, "Liberal Politics and British-Foreign-Office 1906-1912-Overview." International Review of History and Political Science 12.3 (1975): 17–48.

- ^ Glaser, John F. (1958). "English language Nonconformity and the Decline of Liberalism". The American Historical Review. 63 (2): 352–363. doi:10.2307/1849549. JSTOR 1849549.

- ^ R. C. K. Ensor, England 1870–1914 (1936) pp 384–420.

- ^ George Dangerfield, The Strange Death of Liberal England (1935) online

- ^ Kenneth Rose, King George V (1984) pp 113, 121; Ensor. p. 430.

- ^ G.R. Searle, A new England?: peace and state of war, 1886–1918 (Oxford Upwardly, 20040 pp 275–307.

- ^ De Reuck, Jenny (1999). "Social Suffering and the Politics of Pain: Observations on the Concentration Camps in the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902". English in Africa. 26 (2): 69–88. hdl:10520/AJA03768902_608. JSTOR 40238883.

- ^ De Reuck, Jenny (1999). "Social Suffering and the Politics of Hurting: Observations on the Concentration Camps in the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902". English language in Africa. 26 (2): 69–88. hdl:10520/AJA03768902_608. JSTOR 40238883.

- ^ De Reuck, Jenny (1999). "Social Suffering and the Politics of Pain: Observations on the Concentration Camps in the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902". English in Africa. 26 (2): 69–88. hdl:10520/AJA03768902_608. JSTOR 40238883.

- ^ Chris Wrigley (2002). Winston Churchill: A Biographical Companion. p. 311. ISBN9780874369908.

- ^ Helen Irving, To Establish a Nation: A Cultural History of Australia's Constitution (1999).

- ^ Goldman, Lawrence. "Oxford DNB theme: The general election of 1906" online

- ^ Rosemary Rees (2003). United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, 1890–1939. p. 42. ISBN9780435327576.

- ^ Ian Packer, Liberal authorities and politics, 1905–15 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

- ^ a b Sheila Blackburn, "Ideology and social policy: the origins of the Trade Boards Deed." The Historical Journal 34#ane (1991): 43–64.

- ^ Alun Howkins and Nicola Verdon. "The state and the subcontract worker: the evolution of the minimum wage in agriculture in England and Wales, 1909–24." Agricultural history review 57.2 (2009): 257–274. online

- ^ Samuel R. Williamson Jr., "German Perceptions of the Triple Entente after 1911: Their Mounting Apprehensions Reconsidered" Foreign Policy Analysis 7#ii (2011): 205-214 online.

- ^ H.W. Koch, "The Anglo‐German Brotherhood Negotiations: Missed Opportunity or Myth?." History 54#182 (1969): 378-392.

- ^ G.P. Gooch, Before the state of war: studies in diplomacy (1936), pp 87-186.

- ^ A.J.P. Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848–1918 (1954) pp 345, 403–26

- ^ Strachan, Hew (2005). The First Earth War. ISBN9781101153413.

- ^ Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (2014) p. 324

- ^ Keith Robbins, "Greyness, Edward, Viscount Grey of Fallodon (1862–1933)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (2004; online edition, 2011) accessed 5 November 2017

- ^ K.A. Hamilton, "Great Britain and France, 1911-1914" in F. H. Hinsley, ed., British Foreign Policy Under Sir Edward Grey (1977) online p 324

- ^ Gerd Krumeich, "The War Imagined: 1890–1914." in John Horne, ed. A Companion to Globe War I (2012) pp one-18.

- ^ Michael Epkenhans, Tirpitz: Architect of the High german High Seas Armada (2008) extract and text search, pp 23-62

- ^ Margaret Macmillan, The State of war That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (2013) ch v

- ^ Thomas Hoerber, "Prevail or perish: Anglo-German naval competition at the kickoff of the twentieth century," European Security (2011) 20#1, pp. 65–79. abstruse

- ^ Matthew South. Seligmann, "Declining to Gear up for the Great War? The Absence of Grand Strategy in British War Planning earlier 1914" State of war in History (2017) 24#iv 414-37.

- ^ Jean-Pierre Dormois and Michael Dintenfass, eds., The British Industrial Decline (1999)

- ^ a b Arthur J Taylor, "The Economy", in Simon Nowell-Smith, ed., Edwardian England: 1901–1914 (1964) pp. 105–138

- ^ a b Millward, Robert; Bell, Frances Northward. (1998). "Economic factors in the refuse of bloodshed in tardily nineteenth century Britain". European Review of Economic History. ii (3): 263–288. doi:10.1017/S1361491698000124. JSTOR 41377834.

- ^ Clive H. Lee, "Regional inequalities in infant mortality in Great britain, 1861–1971: patterns and hypotheses." Population Studies 45.1 (1991): 55–65.

- ^ J. M. Winter, "Aspects of the impact of the Kickoff Globe War on baby mortality in United kingdom." Periodical of European Economical History 11.3 (1982): 713.

- ^ Barbara Burman, "Made at Domicile by Clever Fingers: Habitation Dressmaking in Edwardian England," in Barbara Burman, ed. The Civilisation of Sewing: Gender, Consumption, and Home Dressmaking (1999) p 34

- ^ Margaret Beetham, A mag of her own?: domesticity and want in the woman's magazine, 1800–1914 (Routledge, 2003).

- ^ Guerriero R. Wilson, "Women'due south work in offices and the preservation of men's 'breadwinning'jobs in early twentieth-century Glasgow." Women's History Review 10#three (2001): 463–482.

- ^ Gregory Anderson, The white-blouse revolution: female role workers since 1870 (1988).

- ^ Carol Dyhouse, Girls growing upward in late-Victorian and Edwardian England (Routledge, 2012).

- ^ Cartriona M. Parratt, "Athletic 'Womanhood': Exploring sources for female person sport in Victorian and Edwardian England." Periodical of Sport History 16#ii (1989): 140–157.

- ^ Roger Ottewill, "'Good and Industrious': Women and Congregationalism in Edwardian Hampshire 1901–1914." Family & Community History nineteen#ane (2016): fifty-62.

- ^ Martin Pugh, Women'south suffrage in Britain, 1867–1928 (1980).

- ^ June Purvis, "Gendering the Historiography of the Suffragette Movement in Edwardian United kingdom: some reflections." Women's History Review 22#4 (2013): 576-590.

- ^ Martin Roberts (2001). United kingdom, 1846-1964: The Claiming of Change. Oxford Upwardly. p. 8. ISBN9780199133734.

- ^ Jane Marcus, Suffrage and the Pankhursts (2013).

- ^ England, Historic. "The Struggle for Suffrage | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk . Retrieved 3 Oct 2017.

- ^ Melanie Phillips, The Rising of Adult female: A History of the Suffragette Movement and the Ideas backside it (Abacus, 2004).

- ^ a b c Knight, Patricia (1977). "Women and Abortion in Victorian and Edwardian England". History Workshop. 4: 57–68. doi:10.1093/hwj/4.1.57. PMID 11610301.

- ^ a b c McLaren, Angus (1977). "Abortion in England 1890–1914". Victorian Studies: 379–400.

- ^ a b c d Thane, Pat (1978). "Women and the Poor Police in Victorian and Edwardian England". History Workshop. six (6): 29–51. doi:10.1093/hwj/6.1.29. JSTOR 4288190.

- ^ Paul Nathanson and Katherine Thousand. Immature (2006). Legalizing Misandry:From Public Shame To Systemic Bigotry Against Men. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 126. ISBN9780773528628.

- ^ Benson, John (2007). "One Man and His Woman: Domestic Service in Edwardian England". Labour History Review. 72 (3): 203–214. doi:ten.1179/174581607X264793. S2CID 145703473.

- ^ Davidoff, Lenore (1973). "Mastered for Life: Servant and Wife in Victorian and Edwardian England". Society for the Written report of Labour History. 73 (27): 23–24.

- ^ Pooley, Sian (2008). "Domestic Servants and Their Urban Employers: A Case Study of Lancaster 1880–1914". The Economic History Review. 62 (2): 405–429. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2008.00459.x. S2CID 153704509.

- ^ Donald Read, Edwardian England 1901-15: order and politics (1972) pp 257-58.

- ^ Marilyn Constanzo, "'One Can't Shake Off the Women': Images of Sport and Gender in Punch, 1901–10." The International journal of the history of sport 19#1 (2002): 31–56.

- ^ Sarah Cosbey, Mary Lynn Damhorst, and Jane Farrell-Beck. "Diversity of daytime habiliment styles as a reflection of women's social role ambivalence from 1873 through 1912." Vesture and Textiles Research Journal 21#three (2003): 101–119.

- ^ Marwick, Arthur (1991). The Deluge. British Society and the Beginning World War (Second ed.). Basingstoke: Macmillan. p. 151. ISBN978-0-333-54846-two.

- ^ J., Stevenson, North. (2012) [2011]. Manner : a visual history from regency & romance to retro & revolution : a consummate illustrated chronology of fashion from the 1800s to the present twenty-four hours (1st U.S. ed.). New York: St. Martin'south Griffin. ISBN9780312624453. OCLC 740627215.

- ^ Laver, James (2002). Costume and style : a concise history. De La Haye, Amy., Tucker, Andrew (Fashion journalist) (4th ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN978-0500203484. OCLC 50081013.

- ^ Olian, JoAnne (1998). Victorian and Edwardian Fashions from "La Mode Illustrée". New York: Dover Publications. ISBN9780486297118.

- ^ Ann Beth Presley, "Fifty years of change: Societal attitudes and women's fashions, 1900–1950." Historian 60#2 (1998): 307–324.

- ^ Kristina Harris, Victorian & Edwardian Fashions for Women, 1840 to 1919 (Schiffer Publishing, 1995).

- ^ Sarah Edwards, "'Clad in Robes of Virgin White': The Sexual Politics of the 'Lingerie'Dress in Novel and Pic Versions of The Become-Between." Adaptation 5#1 (2012): 18–34.

- ^ Alison Gernsheim (1963). Victorian & Edwardian Style: A Photographic Survey. Courier Corporation. p. 94. ISBN978-0-486-24205-7.

- ^ a b R.C.K. Ensor, England, 1870-1914 (1936) pp 309-16.

- ^ Lord Beaverbrook, Politicians and the War, 1914–1916 (1928) ane:93.

- ^ J. Lee Thompson, "Fleet Street Colossus: The Ascension and Fall of Northcliffe, 1896–1922." Parliamentary History 25.1 (2006): 115-138.

- ^ P. P. Catterall and Colin Seymour-Ure, "Northcliffe, Viscount." in John Ramsden, ed. The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century British Politics (2002) p. 475.

- ^ "The Edwardian Sense: Art, Design, and Performance in Great britain, 1901-1910 | Reviews in History". www.history.air conditioning.uk.

- ^ Priestley, J. B. (1970). The Edwardians. London: Heinemann. pp. 176–178. ISBN978-0-434-60332-9.

- ^ J. B. Priestley The Edwardians (1970), pp. 132–139.

- ^ J. B. Priestley The Edwardians (1970), pp. 172–176.

- ^ A.S. Gray, Edwardian Architecture: A Biographical Dictionary (1985).

- ^ David Littlefield, "White City: The Art of Erasure and Forgetting the Olympic Games." Architectural Design 82#1 (2012): seventy–77.

- ^ Vanessa Toulmin and Simon Popple, eds., The Lost World of Mitchell and Kenyon: Edwardian Great britain on Movie (2008).

- ^ see for case "The Lost World Of Mitchell And Kenyon – Episode 1 – 4/6"

- ^ A. R. Ubbelohde, "Edwardian Science and Technology: Their Interactions", British Journal for the History of Science (1963) 1#3 pp. 217–226 in JSTOR

- ^ James Anthony Mangan, ed. A sport-loving social club: Victorian and Edwardian middle-course England at play (Routledge, 2004).

- ^ Tony Mason, "'Our Stephen and our Harold': Edwardian footballers every bit local heroes." The International Journal of the History of Sport 13#1 (1996): 71–85.

Further reading [edit]

- Black, Marking. Edwardian United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: A Very Brief History (2012) extract and text search

- Bowman, Timothy, and Mark L. Connelly. The Edwardian Regular army: Recruiting, Grooming, and Deploying the British Ground forces, 1902-1914 (Oxford Academy Press, 2012).

- Brooks, David. The Age of Upheaval: Edwardian Politics, 1899-1914 (1995) online

- Dangerfield, George. The Strange Death of Liberal England (1935) online free to borrow

- Elton, G.R. Modern Historians on British History 1485–1945: A Critical Bibliography 1945–1969 (1969), annotated guide to g history books on every major topic, plus volume reviews and major scholarly articles. online

- Ensor, R. C. One thousand. England 1870–1914 (1936), scholarly survey. online

- Etherington, Norman. Imperium of the soul: The political and aesthetic imagination of Edwardian imperialists (Manchester Upwardly, 2017).

- Field, Clive D. "'The Organized religion Society'? Quantifying Religious Belonging in Edwardian United kingdom, 1901–1914." Journal of Religious History 37.1 (2013): 39–63.

- Gray, Anne (2004). The Edwardians: Secrets and Desires. National Gallery of Australia. ISBN978-0642541499.

- Halévy, Elie. History of the English People, 1905–1914 (1934), 686pp.

- Hamlett, Jane. At Abode in the Institution: Material Life in Asylums, Lodging Houses and Schools in Victorian and Edwardian England (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)

- Hattersley, Roy. The Edwardians (2005), excerpt

- Hawkins, Alun. "Edwardian Liberalism", History Workshop (1977) #4 pp. 143–61

- Hearnshaw, F. J. C., ed. Edwardian England AD 1901–1910 (1933) online 294pp; 10 essays by scholars.

- Heffer, Simon. The Historic period of Decadence: Britain 1880 to 1914 (2017), wide-ranging scholarly survey.

- Heller, Michael. London Clerical Workers, 1880–1914 (Pickering & Chatto, 2011)

- Kingdom of the netherlands, Evangeline. Pocket Guide to Edwardian England (2013) extract and text search

- Horrall, Andrew. Popular culture in London c. 1890–1918: The transformation of entertainment (Manchester Up, 2001).

- Hughes, Michael. "Archbishop Davidson, the 'Edwardian Crisis,' and the Defense force of the National Church building." Journal of Church building and Land 57#two (2015): 217–242.

- Jenkins, Roy. Asquith: portrait of a man and an era (1964) online

- Lambert, Andrew D., Robert J. Blyth, and Jan Rüger, eds. The Dreadnought and the Edwardian age (Ashgate, 2011). online review

- Marriott, J.A.R. Mod England, 1885-1945 (1948) pp 169–358. online political narrative.

- Meacham, Standish. A life autonomously: The English language working class, 1890–1914 (Harvard Upwards, 1977), scholarly social history. online

- Nowell-Smith, Simon, ed. Edwardian England, 1901–14 (1964), 620pp; 15 broad-ranging essays by scholars.

- Ottewill, Roger Martin. "Organized religion and expert works: congregationalism in Edwardian Hampshire 1901–1914" (PhD. Diss. University of Birmingham, 2015) online. Bibliography pp 389–417.

- Prior, Christopher. Edwardian England and the Idea of Racial Reject: An Empire's Future (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013)

- Read, Donald. Edwardian England (1972) 288pp; survey by scholar. online

- Roberts, Clayton, and David F. Roberts. A History of England, Volume ii: 1688 to the present (2013) academy textbook; 1985 edition online

- Russell, A. K. Liberal landslide : the general election of 1906 (1973).

- Searle, Thousand. R. A new England?: peace and war, 1886–1918 (Oxford University Press, 2004), broad-ranging survey, 952 pp.

- Spender, J.A. Great United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: empire and commonwealth, 1886-1935 (1936) pp 159–401, Focus on Great britain politics

- Thackeray, David, "Rethinking the Edwardian Crisis of Conservatism", Historical Journal (2011) 54#i pp. 191–213 in JSTOR

- Thompson, Paul. The Edwardians: The Remaking of British Club (second ed. 1992)

- Trumble, Angus, and Andrea Wolk Rager, eds. Edwardian Opulence: British Art at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century (2012).

- Ubbelohde, A. R. "Edwardian Scientific discipline and Applied science: Their Interactions", British Journal for the History of Science (1963) one#3 pp. 217–226 in JSTOR

Gender and family [edit]

- Aston, Jennifer, and Paolo Di Martino. "Take chances, success, and failure: female entrepreneurship in tardily Victorian and Edwardian England." Economic History Review seventy.three (2017): 837-858. online

- Mabel Atkinson (1907). "Women and the Revival of Interest in Domestic Politics". The Case for Women's Suffrage: 122–134. Wikidata Q107225563.

- Delap, Lucy. "The Superwoman: Theories of Gender and Genius in Edwardian Britain", Historical Periodical (2004) 47#1 pp. 101–126 in JSTOR

- Dyhouse, Ballad. Girls growing up in late Victorian and Edwardian England (Routledge, 2012).

- Liddington, Jill. Rebel Girls: How votes for women changed Edwardian lives (Hachette Britain, 2015).

- Purvis, June. Gendering the Historiography of the Suffragette Move in Edwardian Britain: some reflections (Routledge, 2016).

- Ross, Ellen. "'Tearing Questions and Taunts': Married Life in Working-Class London, 1870–1914." Feminist Studies 8.3 (1982): 575–602. in JSTOR

- Sutherland, Gillian. "Self-education, grade and gender in Edwardian Britain: women in lower middle class families." Oxford Review of Education 41#4 (2015): 518–533.

- Tracy, Michael. The World of the Edwardian Child: As Seen in Arthur Mee's Children'south Encyclopaedia, 1908-1910 (2008) "+&pg=PR1&printsec=frontcover online

Chief sources and year books [edit]

- Read, Donald, ed. Documents from Edwardian England, 1901-1915 (1973) online

- Almanac Register 1901

- Almanac Register 1902

- Annual Register 1903

- Annual Register 1906

- Annual Register 1907

- Statistical Abstruse of the United Kingdom annual 1901–1909, online

- Wall, Edgar G. ed. The British Empire yearbook (1903), 1276pp online

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwardian_era

0 Response to "A Notable Element in Scottish Art Nouveau Posters Was"

Post a Comment